Why authenticity is bad politics, and bad for politics

Thursday, January 5, 2012 at 10:32PM

Thursday, January 5, 2012 at 10:32PM

1. The Desire for Dave

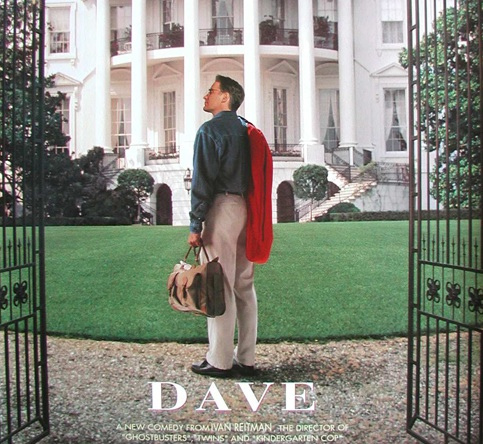

The 1993 movie Dave is about a loveable everyman who happens to bear a remarkable similarity to the president, named Bill Mitchell. Dave is hired to impersonate the president at a public event for what he's told are security reasons, but it's really to serve as a stand-in while the president carries on an extramarital affair. Except the president has a stroke during the liaison and goes into a deep coma, so there is nothing for it but for Dave to continue to act as the president under the control of the president's chief of staff and director of comms.

The President wasn't super popular and his wife hates him, and Dave's innocent enthusiasm is a fresh change from the cynical operator that Mitchell was. Mitchell's popularity starts to climb as President Dave visits a homeless shelter, takes on other feel-good projects, and generally acts as the anti-Mitchell. There's not need to explain the rest of the plot, the key point is this: "Dave" is the embodiment of one of the deepest desires in our culture for a leader who looks just like the current president, except he is selfless instead of calculating, innocent instead of cynical, and honest instead of deceitful. Bonus: it is even implied that Dave has a bigger penis than the actual president.

Our culture is completely captivated by the desire for Dave, and it goes by the term "authenticity".

2. Authenticity lost

The desire for Dave, or what we can call the search for authenticity, has been around for as long as there's been politics, which means it has probably been around forever. But over the last half decade or so, it has been elevated from a legitimate regulative ideal that serves as a check on some of the nastier tendencies of our political culture. It is now held up as the defining virtue of the political leader and the cure for all that ails the body politic. Authenticity, goes the argument, is both good politics (that is, a winning electoral strategy) and good for politics (that is, a way of regaining the trust of the public and its faith in the power of government to work for the common good).

The American writer Joe Klein signposted the trend in his 2006 book Politics Lost, an essay about the decline of authenticity in presidential politics. Klein took his inspiration from what he called Harry Truman's "Turnip Day" speech at the Democratic convention in 1948 that confirmed his nomination for president. Coming on stage after midnight, speaking plainly, simply, and without notes, Truman challenged the "do-nothing Congress" to act upon those views they claim to endorse, and get back to work. Klein thinks we need more Turnip Day moments, more politicians like Truman. He argued that politicians need to "figure out new ways to engage and inspire us - or maybe just some simple old ways, like saying what they think as plainly as possible."

By the time the 2008 election rolled around, the authenticity meme had completely taken hold. For the most part, that election was framed as a battle between competing authenticities: Barack Obama's post-partisan and post-racial authenticity against John McCain's Straight Talk Express. Paired on the VP tickets were Joe Biden's "authentic" tendency to speak first and think later, up against Sarah Palin's moose-hunting mavericky small-town heartland authenticity.

Four years later, the question of the supposed authenticity of the various Republican candidates for the nomination is once again a big issue - and it's something the candidates themselves seem happy to embrace. Here's John Huntsman in a recent NYT profile:

“I think what’s going to drive this election, really, are two things — authenticity and the economy,” Huntsman told me. “I think people have become so disillusioned by the professional nature of politics — the organizations around politicians, the way that politicians approach problem-solving, the way in which they go about their daily business. There has been very little in the way of authenticity in politics in recent years.”

My argument is that Huntsman has it wrong. The problem with politics today is not that there is not enough authenticity in our politics, it is it that there is far too much of it. The push for more authenticity fundamentally misunderstands the nature of mass politics, and contributes to the very problems it is supposed to solve.

3. Politics Unplugged

Like most bad ideas that come North from the United States, the authenticity craze has reached Canada in a somewhat bleached form. It doesn't dominate our political discourse the way it does in the US, but in late November, Allan Gregg -- a man with one of the most interesting CVs in Canadian public life -- delivered a lecture to the Public Policy Forum called "On Authenticity: How the Truth can Restore Faith in Politics and Government." Gregg's claim is that there is a profound disconnect between what we want from our politicians, and what we are getting. Our leaders' most systematic failure, Gregg says, is that "they have not picked up on the electorate's craving for authenticity nor adjusted their behaviour to conform to this new reality."

Gregg even has his own Turnip Day homily to explain just what he's getting at. He tells a story about the night he went to see a folk-rock band in a club in Manhattan when the guitar player's electric pickup broke. Instead of stopping the show to fix the guitar, the band unplugged their instruments, moved closer to one another, and performed an intimate number, with the two singers at one point singing directly to one another in stunning harmony. Says Gregg: "As the last chord was struck, the room literally exploded with rapturous cheering, hooting."

Gregg thinks there's a lesson in this for our politicians. What they need to do, he suggests, is unplug from the way they've always done things and try to reconnect with the electorate. They must drop the prefab talking points designed to "conceal meaning." They need to stop claiming to be the only island of virtue in a sea of knaves. They should cancel all political advertising, and talk straight to the people, saying what they mean and meaning what they say.

How would the electorate respond to a politician who took this approach? Extremely well, Gregg believes. As evidence, he cites a poll showing that three quarters of Canadians would vote for a politician who promised to be truthful 100 per cent of the time, regardless of their party affiliation. "Speaking the truth," he concludes, "is not bad politics." Even better, such an approach would be good politics, and good for politics. "For government to have the capacity and legitimacy to make the kind of decisions necessary to deal with situations that go seriously wrong, requires trust, " he says in his concluding remarks. And he thinks authenticity is the means to that end.

4. Is authenticity good politics?

Allan Gregg gives two examples to support his thesis that the public will respond to authenticity: The election last year of the socially progressive Muslim Naheed Nenshi as mayor of Calgary, and the election in fall 2010 of Rob Ford -- "a leather-lunged, no necked know-nothing" -- to a landslide victory as mayor of Toronto. Here's how Gregg parses these victories:

The evidence suggests that Ford and Nenshi’s very uniqueness -- and that they were not afraid to hide their uniqueness -- made them seem more authentic and believable – basically, the message these politicians sent the electorate was ... “what you see if what you get”. In Rob Ford’s instance, his very crudeness and unrefined nature made him seem “real” and signalled he was not trying to hide anything from voters. The fact that their candidacies horrified traditional power brokers also worked in their favour – basically, if the defenders of the status quo were afraid of them, Nenshi and Ford must be “for the people”.

One initial problem with this is that, in the case of Toronto at least, Gregg is ignoring the recent history of the city's politics. Rob Ford is far from the first crude, loudmouthed rightwinger to win a landslide victory as mayor -- Mel Lastman did it twice, in 1997 and 2000. So perhaps this has more to do with the city's post-amalgamation demographic than it does with any strong public craving for "authenticity". At any rate, Gregg's thesis has hardly been convincingly established.

A more serious problem with Gregg's analysis is that he never actually defines what he means by authenticity. He opens his talk with Polonius' famous "to thine own self be true" line from Hamlet, but he does not seem to grasp the lesson of that passage. Throughout the talk, Gregg insists on treating "authenticity" as a synonym for "truth" or perhaps "honesty". But as Lionel Trilling explains in his book Sincerity and Authenticity, the significance of Polonius and the way we have internalised his message to Laertes is that authenticity has nothing to do with the truth. More precisely, it is about being true to your (idealised) sense of self, not to any external objective facts.

It is hard to overstate the importance of this. The shift from objective facts to self-actualization marks the shift from reason to the emotions as the foundation of knowledge. The hero of a culture of authenticity is not Descartes, or Bacon, or even Hume, but Oprah Winfrey.

It is this fundamental confusion over just what it is he's talking about that leads Gregg to confuse populism with authenticity. It's an extremely common mistake, but it's the sort of mistake that leads him to suggest that Rob Ford is a paragon of authenticity. Ford may in fact be acting "true to himself", in that he doesn't seem inclined to do the usual things we expect of politicians such as hide their antideluvian bigotry or show respect for their entire constituency. But given that Ford is also one of the least honest, and least transparent politicians to appear on the Candian scene in decades, it isn't clear how his brand of authenticity-as-rube-populism is good for anyone, or anything.

5. Authenticity is in the eye of the beholder

You see what I did there, in that last passage? I took someone that some people might hail as refreshingly authentic, and turned his purported virtues into vices. That is, I just wrote an anti-Rob Ford attack ad. And the reason I could get so personal against Ford is thanks to the jargon of authenticity.

Whatever else it may be, a claim to be authentic is a claim about your character, and if you choose to rest your appeal entirely on who you are -- your sincerity, your honesty, your truthfulness -- then you open yourself up to personal attacks. And why should it be otherwise? When it comes to the politics of authenticity, character assassination becomes a legitimate -- if not completely obligatory -- gambit. That is why, despite what supporters of authentic politics like to argue, the focus on authenticity may end up exacerbating the deeply partisan and negative campaigning that voters claim to find so off-putting.

It is important to keep in mind that no one goes into public life with the intention of speaking in sound bites, breaking their promises, and demonizing their opponents. So why do they do it? For the most part, it is because they are soon confronted with the challenge of trying to communicate to millions of people under the continuous and hostile gaze of a political opposition and media that will rip them apart at the slightest misstep.The result is, inevitably, a political culture that is almost completely devoid of spontaneity or intimacy.

What this points to is perhaps the biggest problem with Gregg's thesis, which is the very concept of "politics unplugged." The metaphor of the political sphere as something like a small Manhattan club gets it exactly wrong. National politics is more like an outdoor rock festival with two or three stages, where radically different groups of fans are mixed together to see radically different bands. Pure volume is the only means of survival in such a scenario, and any group that tried to "connect" with the audience by going unplugged would get steamrolled.

But so what? The desire for something else -- for Dave, for Turnip Day, for Politics Unplugged -- is often held up as the stance of noble idealism. It is not. What the pining for authenticity amounts to is just the desire to take the politics out of politics. If this is idealism it is of a very immature sort - there's a reason why Dave is a whimsical Hollywood comedy, not a documentary.

It's an idealism that encourages voter apathy (because "they are all liars", or because "no one speaks to my interests") and obscures this essential truth: We live in an enormous country of 33 million people with any number of deeply incommensurable conceptions of the good.

Canada is not a quaint little village, and the fact that our politicians frequently feel the need to pander to the masses, to change their minds, to break promises, and generally to do what is politically expedient and not govern according to their own idiosyncratic notion of the truth -- this is not a flaw in our system. It is its best feature.

allan gregg,

allan gregg,  authenticity,

authenticity,  politics,

politics,  public policy forum in

public policy forum in  politics

politics