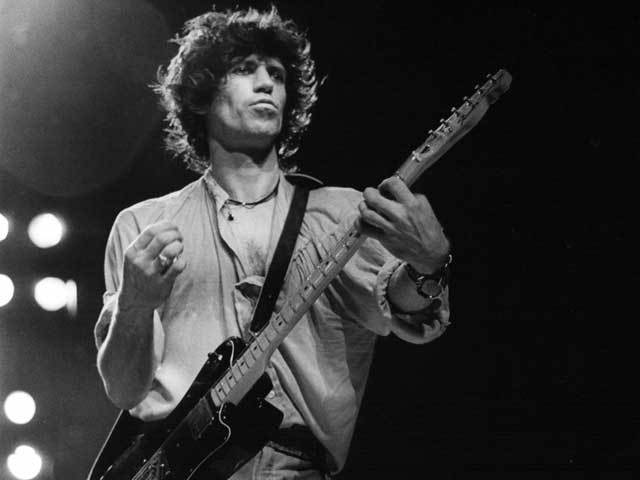

Plagiarism, laziness, and the wisdom of keith richards

Wednesday, August 4, 2010 at 06:38PM

Wednesday, August 4, 2010 at 06:38PM

As long as you turn the set on and put your finger in the air, if there's any songs out there, they'll come through you. It's very easy to get hung up on just the simple mechanics and craft of songwriting rather than the more important thing that real master musicians like the wherling dervishes can tell us about: just letting it go through you and come out the other side. -- Keith Richards, 1983

Sometimes you have to wonder what year the New York Times thinks it is. About seven years after it became a widespread (and widely-reported) probem, Trip Gabriel had a piece this weekend reporting that the digital age is blurring the lines of what constitutes plagiarism for university students. Aside from having nothing remotely new, the piece is an absolute mess, quoting academics tossing out one half-baked theory after another, without even attempting to do some basic analysis of whether any of it makes the slightest sense.

Stop if you've heard this before: the cut 'n paste features of the internet haven't just made it easier for lazy students to cheat. No, the rip/mix/burn online culture has actually changed our definition of the self.

Lord, are we still talking this way? Apparently so:

A anthropologist, Susan D. Blum, disturbed by the high rates of reported plagiarism, set out to understand how students view authorship and the written word, or “texts” in Ms. Blum’s academic language....

In an interview, she said the idea of an author whose singular effort creates an original work is rooted in Enlightenment ideas of the individual. It is buttressed by the Western concept of intellectual property rights as secured by copyright law. But both traditions are being challenged.

“Our notion of authorship and originality was born, it flourished, and it may be waning,” Ms. Blum said.

Look, we may be on the road to some po-mo world where nobody ever says anything new, but the very fact that we find these cases worisome proves that we haven't quite left modernity behind.

We should start by reminding ourselves that plagiarism is foremost a moral question. Sometimes it is illegal (such as when someone makes use of copyrighted material), but the essence of plagiarism is that it is one of a clutch of ethical offences that include fabricating memoirs or news reports, fraud, lying, hypocrisy, and forgery. What unites these is that they all involve some form of misrepresentation.

In many ways, plagiarism is just the flip side of forgery: The forger passes off his own work as that of someone else, while plagiarists pass off the work of others as their own. Plagiarism is an offence that involves the misrepresentation of the self. The reason why we get hung up about these things is because we hold fast to a number of moral ideals about the self. We give these ideals names like uniqueness, integrity and originality, but the motivating principle is what we can call the ethic of authenticity.

As an ethic, it is an injunction to be true to oneself, to place the cultivation of your real self at the forefront of your concern. Our culture remains strongly committed to the ethic of authenticity. Indeed, the reason plagiarism is on the rise is not because we care less about the morality of misrepresentation but -- paradoxically -- because we care about it too deeply.

Because of our commitment to authenticity, we tend to look down on ideas that are borrowed or derivative. We fight over credit for things, partly because there are potential financial or status rewards, but also because we believe there is something profoundly unjust about people receiving credit for books they didn't write or inventions they didn't invent.

But this actually gives us a strong incentive to lie about where we got our ideas. When her plagiarism scandal first hit, Harvard girl wonder Kaavya Viswanathan claimed that she had simply internalized themes and passages from her favourite books. This is the plagiarist's usual gambit, and it is parodied in the film The Squid and the Whale. At the school talent show, Walt announces that he is a about to sing a song he wrote, and proceeds to play a song from Pink Floyd's The Wall. When he's caught, Walt denies that he has done anything wrong. He claims that because he believed that it was the sort of song he could have written, the fact that he didn't was immaterial.

Hilarious, yes, but not far from the truth. Every writer runs into situations where he reads something that seems so obvious, that is so perfectly phrased, that he feels that he would have put it exactly that way, if only he'd thought of it. On these occasions, plagiarism doesn't feel like stealing so much as the appropriation of part of one's true self.

But even this is probably overthinking the problem a bit too much. It's only at the end of Gabriel's piece does a sane voice enter the scene, in the form of Donald J. Dudley, who oversees the discipline office at UC Davis. Most of the cases of plagiarism, he says, did not come from students who were in the thrall of some metaphysical theory of postmodern identity. Instead, they were simply “unwilling to engage the writing process,” i.e. they were lazy.

Or as Keef might say, it's easier just to let the ideas flow through you and out the other side.

Occam's razor remains a very useful tool, even for reporters.

authenticity,

authenticity,  plagiarism,

plagiarism,  tip gabriel

tip gabriel